Just one week after D-Day, Edwin Malcolm Beaton plummeted from the sky toward a small town in France.

Thursday, his family was back in the very same community the airman fell upon in the early morning hours of June 13, 1944.

Beaton was the navigator in a Halifax bomber plane that was shot down over Foncquevillers, a small village 300 kilometres away from Juno Beach.

Sixteen members of the Beaton family made the trek to France to express their gratitude to the descendants of the French resistance fighters who put their own lives at great risk in an effort to save their beloved father and grandfather.

Beaton’s son, Rex Beaton, said his father never forgot the kindness extended to him after the plane crash.

“He felt that he sort of owed the French people something. He was very thankful for their help and that comes through in the letter that he wrote,” Rex said.

Listen to Behind the Headlines about Ed Beaton:

Beaton recounted the harrowing experience he survived in a letter to an inquisitive French historian 40 years after the plane crash.

“Our base was Leeming Bar, 427 Squadron, of R.C.A.F. 6 Group and we were flying the Halifax bomber,” Beaton wrote.

He said they were flying at a rather low level for such a large aircraft — he estimated their altitude to be between 4,000 and 5,000 feet.

“The purpose of our mission was to disrupt railway shipments of arms and supplies behind the new invasion front. It seemed to be that there was greater than usual defensive activity, which was in the form of searchlights and intermittent flak,” he recalled.

Their plane was caught in the searchlights, and Beaton heard a loud banging — like someone hitting the side of the plane with a hammer — before feeling the aircraft lurch. The pilot then shouted for all the men on board to bail.

The 25-year-old jumped from the plane into the abyss and lost consciousness.

“I do not remember any more until I revived in mid-air not far from the ground with my parachute open. I had no way of knowing how many other crew members, if any, had got out as I did not see any other parachutes in the sky before I hit the ground and passed out again,” Beaton wrote.

Five of the seven crew members died in the crash.

Beaton landed hard in a field on the outskirts of a small village.

The bruised and battered young man picked himself up and slowly made his way into the village, rapped on the window of a small house, and held his breath as cautious footsteps approached the door of the home.

“I found myself talking to a man and woman, both having been roused from sleep. Unfortunately, I spoke almost no French and they spoke no English either, so we did not make much sense to each other, but perhaps words were not necessary,” he recalled.

The woman brought Beaton a basin of warm water to wipe the dirt and dried blood from his face, and the couple was able to communicate that it was unsafe for him to stay with them as there were German troops in the area.

Beaton thanked the couple for their help and walked out of the safe harbour of their home, back into the unknown and without shoes. His flying boots had been ripped from his feet when he jumped from the plane.

He walked through the village in the early morning hours, making slow progress as the sun rose over the quiet town. He made it to the edge of the community and fell asleep in a field.

Beaton woke in full daylight to a group of four or five young men working around him, hoeing the field. They weren’t able to converse with him, but they made it clear that they were friends, not foes.

“I was provided, after a few days, with some civilian clothes and a false identity paper, using the passport photo I had with me. I was Henri Kovricki, a Polish labourer on these false papers. They must have been obtained at great difficulty,” he wrote.

Read Beaton’s full letter

Beaton was moved from home to home in the small French village in an attempt to keep him safely hidden, but after 13 days on the run his capture was nigh.

He met an English airman, and the two decided they would set off on foot. But they were caught within their first day of travel.

“As we were both in civilian clothes we were accused of being spies, and I suppose this was more than a little justified. We were caught by the German military, but with the assistance of a collaborator who rode past us on a bicycle and, after speaking to us, became suspicious. When the German patrol showed up he was with them. Anyways, so goes la guerre,” Beaton wrote.

La guerre translates to ‘the war’ in English. So goes the war.

Beaton was apprehended by the German military, then transferred into the hands of the Gestapo. He eventually found himself in Stalag Luft III — a prisoner-of-war camp near Berlin.

Mere months before Beaton’s arrival at the Nazi camp, 76 Allied airmen had escaped Stalag Luft III through a series of tunnels that were painstakingly dug by hand. Their prison break was immortalized in the 1963 film The Great Escape, starring Steve McQueen.

He spent a total of 312 days imprisoned before being freed by the American military.

Beaton returned home to Canada, settling in Regina where he married and had five children.

Honouring Beaton’s legacy

Rex remembers his dad as a quiet and reserved man who didn’t complain much about the horrors he faced during World War II, even when it came to the amount of financial compensation he was offered for his maltreatment.

In 1954, Beaton was offered a one-time payment of 20 cents per day he was imprisoned, which added up to $62.40.

He received an additional $20 for a box-car trip, $39.20 for the 89 days he spent in the custody of the Gestapo, $42.40 for a 53 day hunger march, and $50 compensation for aggravating malnutrition.

“This is the letter to him sending the cheque for $214. And he wrote back to them saying ‘Yeah, I think that’s pretty fair!'” Rex laughed.

Five years later the government agreed to an increase in the compensation, so Beaton received another cheque, this time for $107.

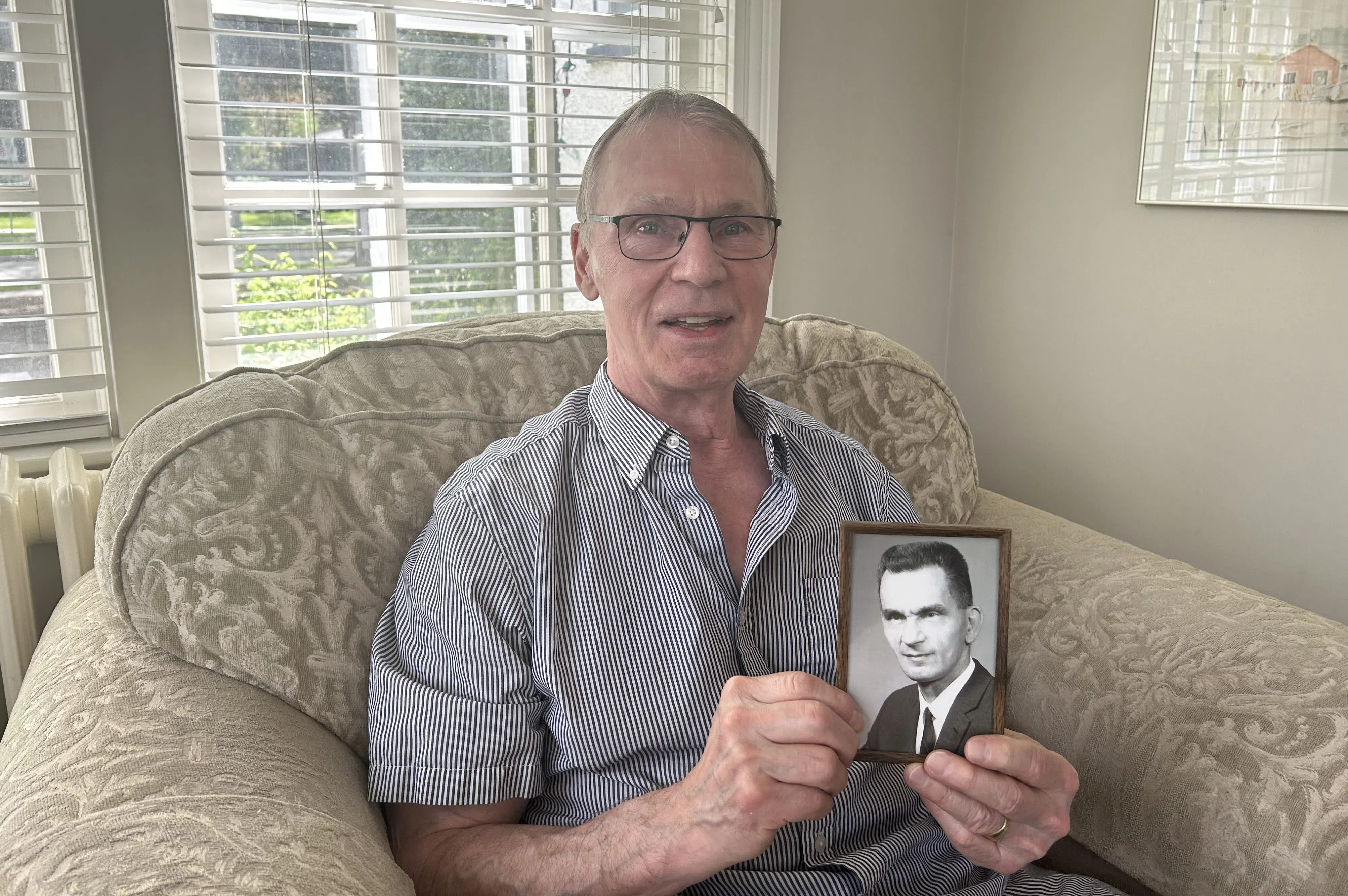

Rex Beaton remembers his dad as a quiet and reserved man who didn’t complain much about the horrors he faced during World War II. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

While the family is able to look back on some of Beatons’ experiences lightheartedly, they are all very much aware of the deep impact of what he survived.

“He didn’t speak very much about the war. There were little snippets here and there, but not alot,” Rex said.

While Beaton’s children are grateful to have discovered the letter he wrote recounting his experience, Rex still finds himself wishing he could have heard this story in its entirety from his father’s own mouth.

“One of my regrets is that I didn’t push a little harder and ask more questions,” he said. “You want to try to respect someone’s privacy, but I kind of regret I didn’t push a little further.”

While they may regret not asking questions before Beaton’s death in 2003, they have done an immense amount of research in the years since.