Measles cases have been confirmed in Saskatoon, with the Saskatchewan Health Authority (SHA) notifying people of an exposure risk.

The SHA said in a news release on Nov. 24 if anyone was at the locations listed below during the specified times they should monitor for measles symptoms for up to 21 days after exposure.

The locations are:

- Princess Auto (2828 Idylwyld Drive North) on Monday, Nov. 10 from 2 p.m. to 6 p.m.

- Krazy Bins (2802 Idylwyld Drive North) on Monday, Nov. 10 from 2 p.m. to 6 p.m. and

- Once Upon a Child (331 105th Street) also on Monday, Nov. 10 from 2 p.m. to 6 p.m.

The SHA says that from March 14 to Nov. 19, 107 measles cases had been reported in Saskatchewan in 2025, with 95 of those cases in people who were unvaccinated and the majority of cases in children and young people aged one to 17.

There have been no deaths in the province from measles, but 10 people needed treatment in hospital and two people had to receive intensive care.

Read more:

- Health-care officials disappointed with measles re-emergence in Canada

- Murray Wood: What would our grandparents think about the return of measles?

- Canada needs to invest in public health to regain measles elimination status

What are the symptoms of measles?

The SHA said that the symptoms of measles include fever, cough, runny nose, red eyes, fatigue, irritability (feeling cranky or in a bad mood), small, white spots (known as Koplik spots) inside the mouth and throat, and a red blotchy rash which develops on the face and spreads down the body about three to seven days after symptoms begin and can last four to seven days.

The SHA said anyone who has any of the listed symptoms and was at any of the listed locations during the identified times, should call HealthLine811, their primary care doctor or nurse practitioner.

Anyone in medical distress, should go to an emergency room or call 911, and identify they may have been exposed to measles.

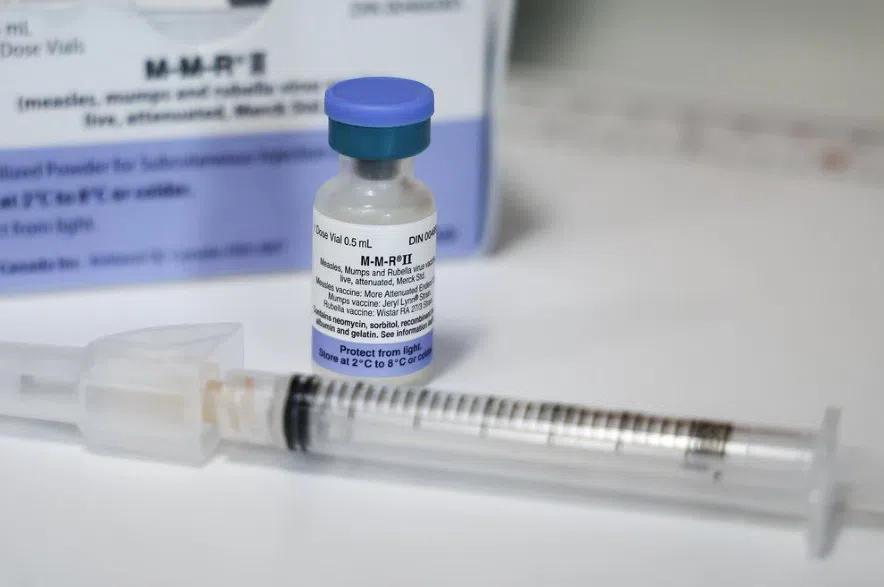

The health authority also said that measles can be prevented by the safe, effective and free measles vaccine and with two doses, the vaccination is almost 100-per-cent effective

“Immunization is your best tool against measles, and two complete doses is what you need to have full vaccination. One dose is not enough,” the SHA’s Dr. David Torr said.

“Once immunized, the measles vaccine is extremely efficient, over 90 per cent of protection both against actually getting the infection and certainly against getting any complications or even death from measles.”

The second dose is especially important for people born in or after 1970.

Why is measles dangerous?

Measles is highly contagious and can spread very easily by breathing contaminated air after an infected person coughs or sneezes, or by touching a contaminated surface such as a doorknob or a shopping cart.

In rare cases can lead to respiratory failure, swelling of the brain and death.

If anyone breathes the contaminated air or touches a contaminated surface and then touches their nose, eyes or mouth, they can become infected.

The virus can live up to two hours in the air or on surfaces in a space where an infected person coughed or sneezed.

It can spread to others from four days before a rash appears until four days after a rash develops. Through this period, people need to stay in strict isolation to avoid spreading the infection.

Canada officially lost its measles elimination status in early November.

The country eliminated measles in 1998 and maintained that status for more than 25 years, meaning there was no ongoing community transmission and new cases were travel-related.

The Pan American Health Organization revoked the status after confirming there has been ongoing transmission of the same strain of measles for more than one year.

But since Oct. 27, 2024, the virus has spread to more than 5,000 people in Canada, including two infants in Ontario and Alberta who were infected with measles in the womb and died after they were born.

Public health and infectious disease experts attribute the return of measles to declining vaccination rates, stemming from misinformation-fuelled vaccine hesitancy and distrust of science, as well as the disruption of routine immunizations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

— with files from Canadian Press

Read more: