A thin wind moves through the old poplars of Nutana Cemetery, rustling the last leaves of autumn.

Beneath them, etched names and dates drift in and out of shadow in the late-afternoon light — traces of the first Saskatonians, resting where the city began.

“A cemetery is kind of an archive,” mused Saskatoon’s city archivist Jeff O’Brien, looking out across the quiet rows of headstones.

“With the words carved in stone. Names and dates and places. For an awful lot of people, this is the only permanent record there will ever be of their existence here on Earth.”

Every grave in Nutana Cemetery tells a story of beginnings and endings on the prairies. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

The Nutana Cemetery has stood here since 1884, before the city even had bridges, when the Temperance colonists carved a small settlement out of the prairie.

“You can understand why they chose this place,” O’Brien reflected. “When you look out across the river, it’s a beautiful spot.”

Back then, this patch of land was a lonely edge of the world. A tiny flyspeck of civilization surrounded by endless grass and sky.

And on that lonely frontier, the city’s first documented stories of death unfolded.

Listen to the story on Behind the Headlines:

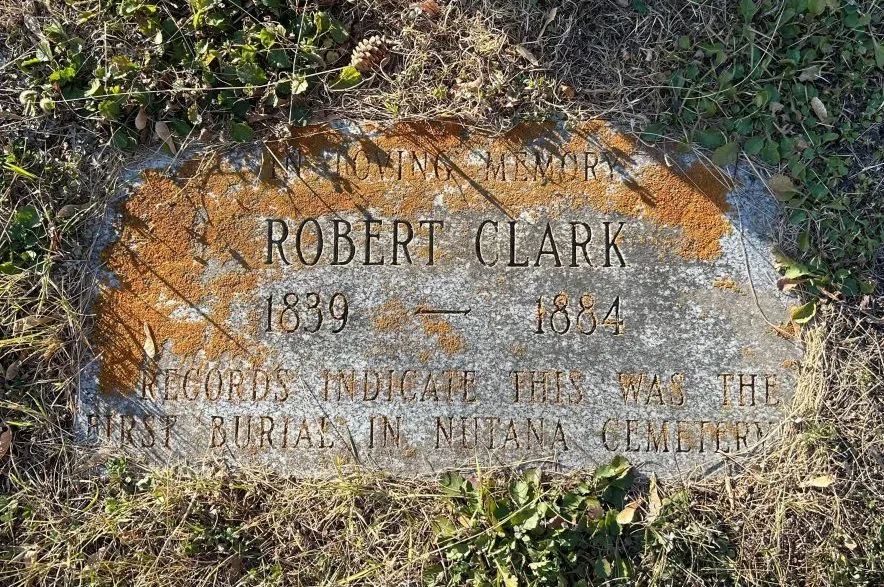

Robert Clark and the prairie fire

The stories held in these grounds begin in 1884, with a man named Robert Clark.

Every story starts somewhere. For Nutana Cemetery, it began with Robert Clark. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

That summer, the prairie grass was dry as straw. When fire came — as it often did — the settlers of the colony dropped everything to fight it.

“It’s all hands on deck,” O’Brien said. “They’re working like crazy to put it out.”

Robert Clark was among them.

The smoke must have stung his eyes; the wind carrying sparks that glowed like red stars.

In the middle of the chaos, Clark collapsed. The others dragged him to shelter, but he developed pneumonia.

“When it becomes obvious that he’s not going to survive,” O’Brien recounted, “his son goes racing down to Moose Jaw because his wife and the rest of the family are coming in on the train. He collects them, comes back up, and they get back to Saskatoon just in time for Robert to die.”

Robert Clark fought flames that swept the prairie in 1884 and became the first to rest in what would become the Nutana Cemetery. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

The family buried him here, on “this lovely little stretch of otherwise unoccupied prairie.” O’Brien gestured across the field. “This is the beginning of the cemetery.”

But Clark’s resting place hasn’t always been here. “In fact,” O’Brien explained, “this whole two lines of graves that we can see in front of us, where they are now, is not where they were buried.”

Originally, the graves lay closer to the riverbank. “In 1968 to 1970, they dug all those graves up and moved them back here,” he said. “They were in danger of being destroyed by the slumping riverbank. Because the problem when you build something next to a riverbank is that eventually, it falls into the river.”

The South Saskatchewan River continues to shape the cemetery’s edge. In the late 1960s, more than a dozen early graves were moved back from the bank to keep them from sliding into the water. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Now the settlers rest a little farther from the edge. Safe, for the moment, from the slow pull of the river that shaped the city they built.

Neville Pendygrasse and the river

“This guy here is Neville Pendygrasse,” O’Brien said, motioning toward a headstone lying low in the golden grass, dark and polished.

The stone is unmistakably new, its sharp edges unmarred by time. “He died Aug. 9, 1887. He fell off the ferry and drowned.”

A new stone marking an old story. Neville Pendygrasse drowned in the South Saskatchewan River in 1887. His mother later settled nearby, never far from her son’s resting place. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

In those days, the South Saskatchewan River was the city’s lifeline.

“Before there were bridges or railways, the only way to get back and forth across the river was on the ferry,” O’Brien explained. “It used to run across from the foot of Main Street into what’s now Victoria Park.”

No one knows exactly how it happened. Maybe a slip on the deck, a gust of wind or a sudden panic in the cold, fast current.

Regardless, Neville’s story ended here, in this rough and unforgiving place that the settlers were still trying to tame.

“The even more tragic part,” O’Brien said, “is that his mother and sister were coming to Saskatoon. They arrived shortly after to be greeted by the news that her youngest son had died tragically.”

She stayed anyway.

“Mrs. Pendygrasse took up a quarter section just over here on St. Henry,” O’Brien said. “In my romantic imagination, I feel she built her sod house so she could look out her door and see her son when she got up in the morning.”

You can almost picture her: a figure in a long dress and shawl, standing in the doorway of her sod house, looking longingly toward the place where her boy rests.

Ted Meeres and the blizzard

Some deaths here feel almost impossible, accidents under circumstances that seem to belong to another world entirely.

“This is Ted Meeres,” O’Brien said, pointing to a stone standing proudly near a bluff of trees.

Rust-coloured lichen freckles the pale stone. Carved flowers curl delicately along its edge, symbols of a life once tenderly remembered.

Ted Meeres left a party to check his cows in a storm and vanished into the night, never to return. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

“Poor ol’ Ted was a bachelor farmer living just off Broadway in 1888. A young fellow from England,” O’Brien explained.

It was a Saturday night. A few neighbors had gathered for a Temperance party — no alcohol, just laughter, lamplight and fiddle tunes muffled by the storm outside.

When the wind howled against the windows, Ted pulled on his coat.

“He decided he was going to go across the street, literally across the street, to check on his cows,” O’Brien said.

He never made it.

“They found him a couple of days later, about five miles south of here, frozen solid.”

O’Brien shook his head. “Can you imagine getting lost, even in a snowstorm, on Broadway? You’ve got streetlights and everything everywhere now. But back in the day… This poor bastard goes out for a walk and gets lost in the snow.”

Now, he rests under one of the prettiest headstones in the cemetery — the bachelor farmer who simply vanished into the white.

Rosetta Lasher and the children of Nutana

If you walk the rows of Nutana Cemetery slowly enough, you start to notice how small some of the markers are. Narrow, rounded, barely the height of the grass.

Many hold only a word or two: Baby, Infant son, Daughter.

One of more than 50 infant burials in Nutana Cemetery. Each stone, a love story too brief to be told in full. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

The earliest settlers brought hope with them across oceans and prairie, but they also brought with them a truth as old as time: life is never guaranteed.

“There are 162 known burials in Nutana Cemetery,” O’Brien said. “Of those, 51 are babies, and another 14 are children under 16 years of age.”

The numbers are staggering when you stop to think about them. Fifty-one small graves. Fourteen more belonging to children who never made it to adulthood.

The grave of 10-year-old Oliver John Caswell, one of 14 children buried here. Each stone marks a family forever changed. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

“Historically,” O’Brien explained, “throughout sort of the whole of human history, what we see is that child mortality is about one in two. One in two children does not grow up to be an adult, and those numbers only really started to come down in the last couple of hundred years.”

He paused before one grave in particular.

“We’re standing beside the gravestone of Rosetta Lasher,” he said. “She was 20 when she died in 1906, and she died in childbirth. She had child bed fever. It struck you after the birth. You had a fever and a couple of days later, you died.”

Rosetta Lasher was just 20 when she died in childbirth in 1906. Her story echoes that of many women who risked everything to bring new life. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

It’s hard not to imagine her, a scared young woman holding her newborn for a brief, fevered moment before slipping away.

“Ironically,” O’Brien added, “it was caused by doctors who didn’t understand that washing your hands was a good way to keep from spreading disease.”

Rosetta’s grave is simple, but it tells the heroic story of countless women who laboured and loved, knowing the dangers that came with bringing a child into the world.

“Throughout human history, childbirth and pregnancy have been danger zones for women,” O’Brien said. “Advances in public health, germ theory, all these things we take for granted now. They’ve gone a long way toward reducing those numbers. In Canada now, the infant mortality rate under one year old is something like 0.5 percent. That’s a success story.”

The graves of more than 50 infants are scattered among the rows, quiet reminders of how fragile early prairie life could be. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

The success feels fragile standing here, surrounded by these names. Each stone marks a story cut short.

And for every mother or child whose name has been worn away by weather and time, Nutana holds their memory still, safe beneath the grass.

Bessie Trounce and the letters home

Not all of the graves in Nutana Cemetery are marked. Some stories here have slipped quietly beneath the grass, like that of Bessie Trounce — one of Saskatoon’s earliest settlers and one of its brightest spirits.

“One of the saddest stories of Nutana Cemetery is Bessie Trounce,” O’Brien said. “Bessie and her family came to Saskatoon in 1884, and they were the life of the party. The Trounce house was the party house in Saskatoon.”

You can clearly imagine the scene: laughter spilling into the cold prairie night, lamplight glowing against frost on the windows. For a short while, the Trounces made this lonely outpost feel like a community.

Then, in 1887, tragedy struck. “She died in childbirth,” O’Brien said simply. She was only in her twenties. Her husband, grief-stricken, went back to England to prepare to move his family back overseas, but died there soon after.

“An uncle came and collected the children and took them back to England,” O’Brien added. “And then, there’s no more Trounces in Saskatoon.”

Bessie’s grave has long since vanished.

“A lot of the burials here are unmarked,” O’Brien explained. “There’s burials that we know about, but they’re unmarked. We don’t know where they are. And Bessie Trounce’s is one of those.”

Somewhere beneath this ground lies Bessie Trounce, one of Saskatoon’s earliest settlers. Her grave is unmarked, but her letters home helped preserve the city’s history. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

It’s a haunting irony. “So much of what we know about Saskatoon in that era,” O’Brien said, “is because Bessie Trounce wrote letters home all the time, and those letters ended up back in Saskatoon in the archives.”

Her words survived, even if her marker did not.

Somewhere beneath the poplars, beneath the drifting leaves and the cool October air, she rests — the woman who helped build a community, and who, through her letters, still whispers the story of those early days.

The cemetery game

As the afternoon light began to fade, O’Brien turned the conversation inward.

“My wife and I like to go to cemeteries,” he said. “I should say, I like to go to cemeteries, and when I got married, I dragged my wife along with me.”

They call it ‘the cemetery game,’ a quiet ritual of remembering.

“We walk the rows, and we read the names and the dates, and we feel sad for the people,” he explained. “We tell their stories to each other as we go. ‘Oh, look, there’s four children. They all died on the same day. It must have been an accident.’ That kind of thing.”

He looked out over Nutana Cemetery one last time.

“When I talk about a cemetery being an archive, that’s what I mean,” he reflected. “It’s a place where memory lives on, beyond the life of the people and beyond the memory of the people who even knew them.”

And as the wind dances gently through the grass and over the stones, those memories — fragile, human, eternal — stay right where they’ve always been.