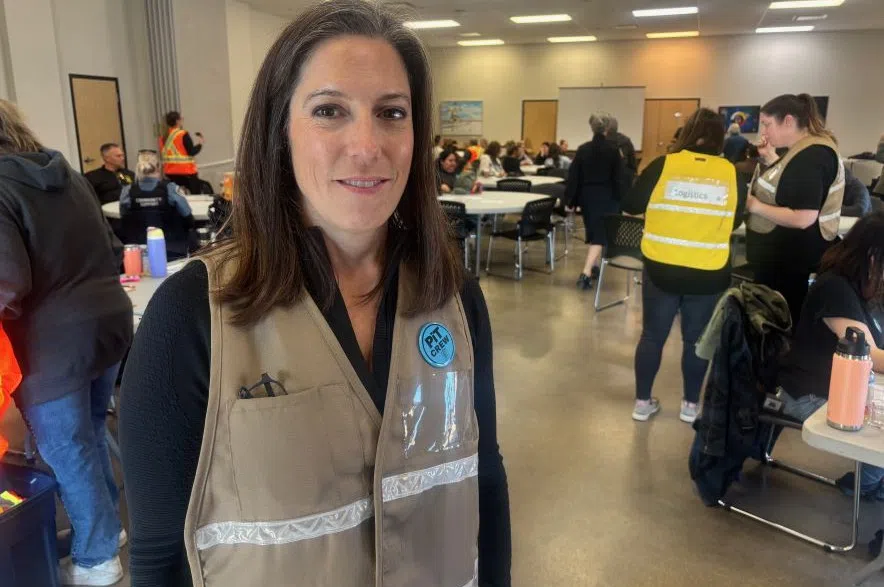

Leslie Anderson, Saskatoon’s director of planning and development, greeted me in the bustling, busy common room on the ground floor of the Station 20 community centre in Saskatoon’s Pleasant Hill neighbourhood on a warm and sunny Thursday afternoon.

As we briefly chatted, I noticed the large room buzzing with people — team leaders dressed in high-visibility vests, members of the Saskatoon Fire Department directing operations, and volunteers waiting to confirm their registration to help with this year’s point-in-time homeless (PiT) count; a process I wanted to take part in and observe.

Read more:

- Point-in-time count identifies 315 homeless children in Saskatoon

- Caswell Hill residents concerned about permanent emergency shelter site

- Saskatoon council considers budget options for affordable housing strategy

What is the PiT count?

The point-in-time homeless count is an attempt to identify the number of people who are homeless in a city at a given point in time. It used to be done every three years, but is now completed on a yearly basis, kind of like a census.

Using standardized national methodologies adapted to reflect local context, the point-in-time count provides insights into demographics, service use, and the pathways that lead people into homelessness through a series of questions that volunteers ask.

The count can be influenced by factors like weather, volunteer training, and the types of questions asked. This year, Anderson said 260 volunteers signed up to take part in teams of three. There were four shifts throughout the day for people to come in and go out and conduct the count throughout the city.

The teams were all given maps and assigned a specific area of the city to walk through and to attempt to speak with everyone they met, while identifying themselves as a volunteer doing a study on housing and homelessness.

The numbers gathered are not only used by cities to decide on resource allocation, but they’re also submitted to the federal government, which funds the count.

Information gathered by volunteers in October, 2024 showed there were 1,499 people who were homeless in the city, nearly tripling the previous count done in 2022.

Preparing for the count

Behind the volunteer registration desk were several tables with boxes of Halloween candy, fruit snacks, and water bottles. Next to them was a portable trolley with packages of cigarettes, matches, and sandwich sized plastic bags.

The treats went into the bags, along with transit passes and cards with the numbers of outreach organizations. Each team leader then received a shopping bag with one package of cigarettes, along with at least a dozen small bags.

The snacks and smokes were for survey participants as a “thank you” for answering questions.

Members of the Saskatoon Fire Department then held a short safety briefing where volunteers were told not to approach large encampments, stick to their assigned areas, and not leave their groups.

“We really just tell people ‘beware of your surroundings, you’re working in a group so keep your eyes open,” said Anderson.

Once that was completed, I introduced myself to the team members, including Celene Anger, Saskatoon community services general manager; Nola Stein, an urban design city project manager, and Krista-Dawn Kimsey, the team leader, who worked at The Mustard Seed shelter.

Anger’s job was to ask a series of pre-set questions of everyone we encountered along our route, while Stein wrote down the answers. The four of us then left on our assigned route: the railway track corridor stretching from Avenue S South, north to Idylwyld Drive, about a five-kilometre stretch.

A woman in a sleeping bag on the ground speaks with team member Celene Anger, during this year’s point-in-time homeless count in Saskatoon on Oct. 16, 2025 (Lara Fominoff/650 CKOM)

Places to stay in short supply

Heading north along the railway tracks from Station 20 towards 22nd Street and Idylwyld Drive, we quickly came across a woman lying on the pavement in a red sleeping bag; her head covered and her belongings in shopping bags beside her.

She answered the questions about her age, how long she’d been in Saskatoon, whether she identified as male, female, or other, and if she was First Nations, Métis, or Inuit.

When asked whether she had a place to stay, she answered that she’d tried to find a spot at The Mustard Seed, but was unable to. Calls to the STC Wellness Centre and The Mustard Seed shelter indicated they were full and there were long waiting lists.

Less than a block away, we found a man sitting on the ground, slumped against a garage, barely conscious but still willing to speak with the team. His hands were clasped together, a large, infected looking wound on one of his fingers that looked like a black cigarette burn. He too, could not find a place to stay for the night.

The team was tasked with speaking to everyone along the railway corridor spanning from Avenue S to the south, to Idylwyld Drive to the north on Oct. 16, 2025. (Lara Fominoff/650 CKOM)

Further along the tracks near Avenue F South, was one of the most concerning encounters we observed occurred after the team spoke with a woman living in a black tent.

Shortly after she answered the survey questions, a man in a battered black KIA SUV pulled up next to the tent, and entered it to retrieve a package which he placed in the back of the vehicle. He then pulled the woman out by her arm, and ushered her into the front seat and drove away with her.

There were many others the team met and spoke with including a man dumpster diving who was one of the few able to get a space at the Salvation Army for the night.

There was also a group of five people dressed in red and black colours sitting behind a popular restaurant near Idylwyld who questioned the need for the PiT count, and one older woman lighting up her crack pipe and smoking whatever was in it in front of us.

Then there was the woman sitting in a small patch of grass next to a hotel, her blue and white toothbrush in a used, soapy plastic pop bottle. All she asked for was some water.

A few others the team spoke with did have a home, or at least somewhere to go — for now.

The last young man we met was just 19 years old. He told us he’d been taking a nursing course, but had to drop out because both his mother and father were dying. He dad had recently passed away and his mom he believed, was not far behind. Struggling to speak at times because of a stammer, he wondered out loud whether he’d even have a home after she passed away.

My time with the volunteers ended after as we walked back to Station 20 for a bathroom break and to refill the snack bag and cigarettes for the other half of the route.

According to Anderson, the information gathered by all of the volunteers will be compiled, cross-checked and then processed into numbers.

It’s not clear at this time when the final numbers will be released, however a report is expected sometime in the next few weeks.

Read more: