Long before staff sergeant Terry Laverty picked up his Saskatoon police badge, he picked up a pencil.

Laverty has always had artistic talent, sketching during his high school and post-secondary education before getting into policing. But while he was working as an investigator with the Saskatoon Police Service’s sex crimes unit, a composite sketch presented at a conference in Calgary grabbed his attention.

Read more:

- Man found dead in river identified, foul play not suspected: Police

- Girl, 12, facing charges after allegedly threatening boy with knife: Saskatoon police

- Debden man facing impaired driving charge after three-vehicle collision in Saskatoon

“It just intrigued me that this was still a viable tool utilized by police services,” Laverty said. “I immediately reached out and was able to kind of latch on to that type of training.”

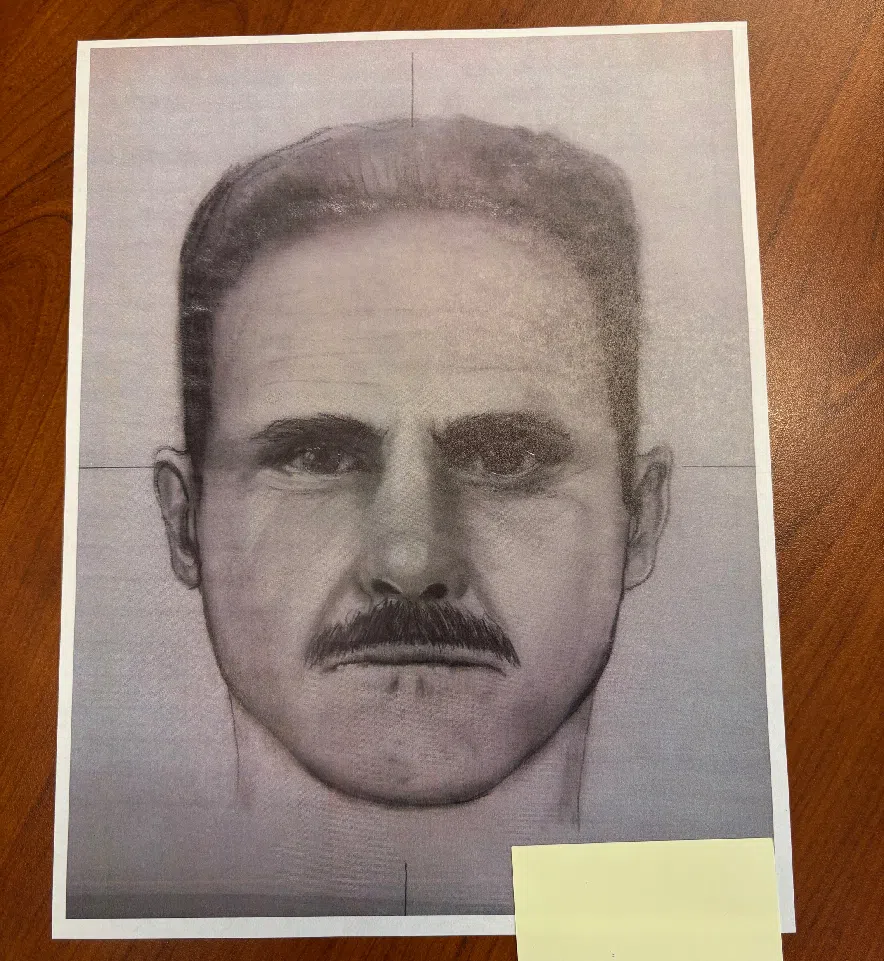

A composite sketch is a visual representation of someone’s memory. The sketch is a structured drawing, based on the description given by a victim or a witness, and Laverty said it’s kind of similar to drawing a caricature.

Listen to the story on Behind the Headlines:

“You’re taking elements of a person – their visual description – and putting them all together to create a final image that hopefully somebody would recognize,” Laverty explained.

Composite sketches can take hours to craft, and Laverty said the process starts with an interview, to help the witness recall as much as they can from the event. After that, he hones in on the specifics of the description.

Laverty said it’s not as simple as just asking someone to describe what the suspect looked like. He said sketch artists provide tools to help guide the interview subject through the process.

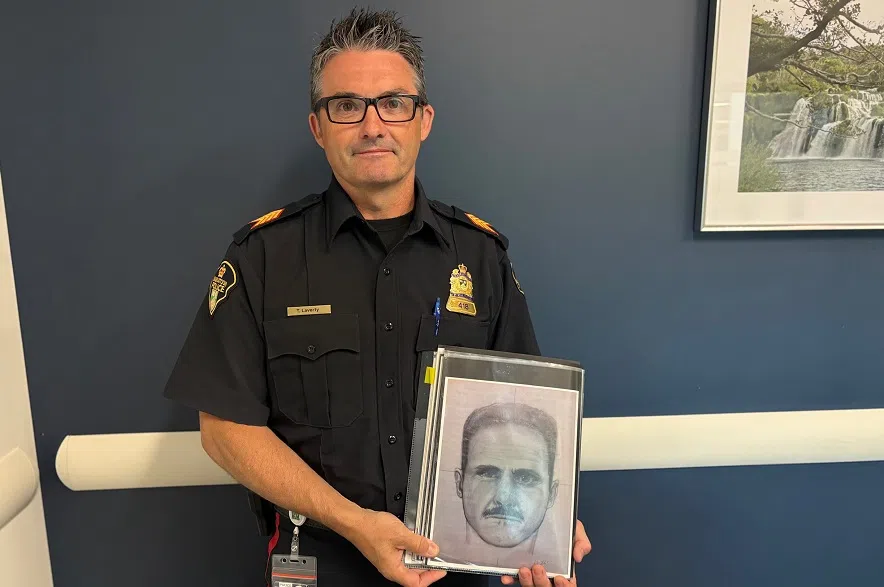

Staff sergeant Terry Laverty has crafted around 30 composite sketches for the Saskatoon Police Service, creating about two to four each year. (Mia Holowaychuk/650 CKOM)

“Average people that don’t study art wouldn’t really look at an earlobe, or wouldn’t look at an eyebrow or an eye or a mouth or the structure of a nose,” Laverty said.

Laverty said one important question he frequently asks is: “How did this person make you feel?”

“It gives us an idea of what the person is, (and) how we can stylize the image to a list of what they were maybe feeling at the time,” he said, explaining that witnesses often describe suspects using terms such as angry, overconfident or sheepish.

“Memory is very linked to emotion,” Laverty said. “It may help them recall some more of the memory of the event, details or the description of the person.”

When asked about the accuracy of composite sketches, Laverty said he defers to the witnesses, as they play the most crucial role in the process.

“As far as I’m concerned, my sketch is complete when the witness says it’s complete,” he said.

Laverty has crafted around 30 composite sketches for the police service, creating about two to four each year.

With the advancement of technology such as video surveillance, he said the need for a sketch is reduced in many cases.

Laverty said sketches are used when there are no other means of identification. They are not crafted often, and are only used in serious cases.

“If you’re throwing out drawings every week, it’ll be hard for people to place and put them into the situation and to the criminal file that was involved,” he said.

Laverty has seen success with his sketches, reflecting on a particular case involving a double robbery in Saskatoon.

“I happened to be working on one of the sketches at the time, and an officer had walked by my desk seeing me kind of finishing up my sketch, and he immediately said ‘I know who that is,’” Laverty said.

“It was amazing, because the sketch itself wasn’t great,” he said, adding that while it wasn’t the most descriptive drawing, some significant characteristics led to the arrest.

Composite sketches are another tool in the toolbox for investigators, Laverty explained, and they are created with the hope of not only helping victims, but leading to an arrest to hold perpetrators accountable.