The Saskatchewan sun can be merciless in July. It’s the kind of heat that settles on your back like a weight, soaks your clothes with sweat and blurs the air above the fields.

But even on the hottest, most breathless Saturdays of summer, Brenda Cheveldayoff laces up her boots, wraps herself in her long Doukhobor skirt, vest, and shawl, and leads another group down into the ravine behind her family’s farm.

The descent is slow, the path uneven — but each step down the ravine is a journey backward, to a time when calm winds and sheltering earth meant survival for Doukhobor settlers. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

“A long time ago, when I first started tourism, I would do four tours a day and walk down the hill four times a day,” she said. “Going up is hard. There’s a secret going up… Don’t talk! You save your breath.”

Listen to the story on Behind the Headlines:

The path is steep and uneven. You have to watch your footing. You have to take your time.

Each descent is a journey into the past — toward a 436-square-foot dugout carved into the earth more than a century ago by Doukhobor settlers who fled persecution in Russia in search of peace on the Canadian prairie.

Read more:

- Guitar-making school in rural Sask. attracts students worldwide

- From plates to pendants: Saskatchewan artist makes jewelry from dishes

- Local author inspires young writers at Saskatoon elementary school

Hand-painted signs carry the names of Doukhobor families — markers of presence, resilience and legacy rooted in the prairie soil. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

It’s where Cheveldayoff’s great-grandfather lived as a boy.

It’s where stories took root and never quite left.

In those early days, she would find Donna Choppe at the top of the hill, waiting like clockwork to carry on with the rest of the tour. Her friend and accomplice in preserving history would take over, and Cheveldayoff would step back into the present.

“When it was 100 degrees outside, I was literally wringing wet,” Cheveldayoff recalled with a laugh. “I’d go to the vehicle and take off my vest and my shawl and turn the air conditioner on and get cooled off until I had to go back down again. We’d meet at the Canadian flag and start all over again.”

To live without violence, the Doukhobors once gathered in defiance and burned their weapons in a symbolic blaze. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

This is how the Doukhobor Dugout House came to life. Not from a polished boardroom plan, but from sweat, stubbornness and a friendship forged in the fire of shared purpose.

They didn’t set out to build a nationally recognized historic site. They just couldn’t bear to let it be forgotten.

Where memory lives in the dirt

There was no signage. No path. Just a quiet farmyard and a woman who stumbled across a magazine article that changed everything.

“When my father passed away, I was cleaning out this building, and I came across a National Geographic magazine,” Cheveldayoff said, standing inside the old quonset that now holds a small gift shop and museum.

Inside the pages, she found something unexpected: her grandfather, giving an interview about the site and its significance — speaking of the very land she had grown up on.

“And I thought, ‘Hmm, is there something to it?’” she said. It turns out there was.

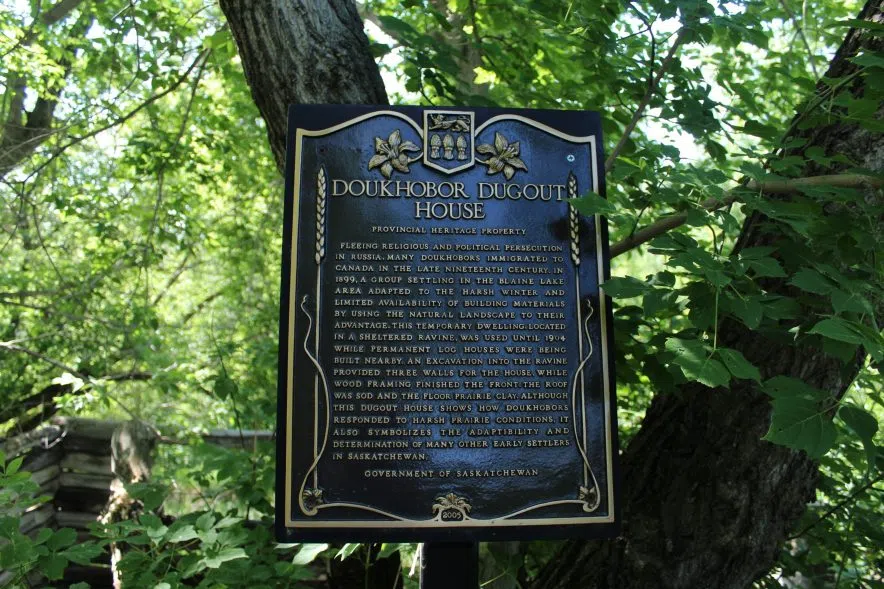

When Saskatchewan recognized the site as a provincial heritage treasure, it wasn’t just about preserving a structure — it was about honouring the courage of those who carved life from the hillside. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Looking back, the clues had always been there.

As a child, she and her cousins would play on a sod-covered mound down the hill. Her grandfather would scold them, telling them to stay off it. It wasn’t a playground. But the kids, caught up in imagination, couldn’t resist. It felt like a secret fort — a hidden place. And in a way, it was.

That ruin was a surviving footprint of the original Doukhobor settlement, a story literally carved into the side of the hill.

She called the University of Saskatchewan and the Heritage Foundation. They came out, dug in and confirmed it.

“We got the archeological facts because archeology doesn’t lie,” Cheveldayoff said proudly.

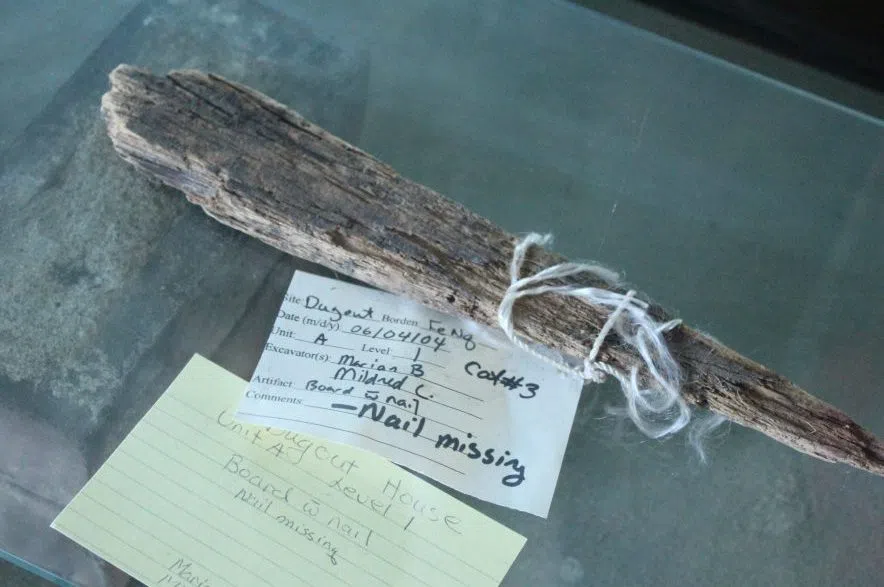

When archaeologists came with trowels and brushes, they didn’t just find artifacts — they uncovered stories buried deep and confirmed what Cheveldayoff always knew: this place mattered. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Her father, Sam Popoff, had grown up hearing the stories and passed them down like treasured heirlooms. But more than stories, he gave her a feeling for the land. Because while this place is historic, it has never been still.

As a child, Popoff used to fly down the ravine on a wooden sleigh, with his dog Spot pulling him back up again. In the winter, he and his friends played hockey on the frozen pond nearby. They didn’t have pucks, so they used dried horse poop from his beloved horse Queenie.

Today, Cheveldayoff still has that old sleigh. The largest tree in the ravine is named after her dad. And the pond he once skated on is still there too — quiet and unassuming, like a memory waiting to be stirred.

“My dad was forever touring people around here,” she recalled with a soft smile. “People would say, ‘Oh, we remember your dad.’ I’d say, ‘Yeah, he probably got off the tractor and drove everybody around instead of seeding, right?’”

There was even a rainy afternoon when Cheveldayoff convinced him to give a full, four-hour tour on camera. That recording later became a priceless resource for researchers mapping the site.

“They used it. They listened to him. And then they went researching throughout the ravine,” she said.

Brenda’s father, Sam Popoff, gave more than memories — he gave her the rhythm of this land. He toured guests, shared stories and once traded a rainy day for a four-hour oral history. (Submitted)

Long before it became a heritage site, this land was a home.

A grandfather guarded it, a father shared it, and a daughter — with her friend at her side — brought it back to life.

The voice in the Prayer Home

Donna Choppe remembered everything.

She labelled things meticulously and questioned every object Cheveldayoff tried to throw away — including, infamously, a bag of old wooden clothespins.

Donna Choppe wasn’t just a volunteer — she was the soul of the Doukhobor Dugout House. For 17 years, she catalogued, labelled and preserved a fading culture. (Doukhobor Dugout House National Historic Site of Canada/Facebook)

“I remember her accusing me of throwing them out,” Cheveldayoff said with a laugh. “I said, ‘Donna, I never touched them. You bring so much crap here all the time!’ We got into an argument.”

Years later, after Choppe passed in 2020, Cheveldayoff was sorting through the gift shop when she spotted them: the clothespins, tucked away just where her friend had left them. She never moved them again.

That’s the thing about Choppe. She left little pieces of herself everywhere; not just in objects, but in the spirit of the place.

In every artifact, every laugh and every long summer day spent preserving the past, Brenda Cheveldayoff and Donna Choppe built more than a historic site. They built a friendship that became part of the land itself. (Doukhobor Dugout House National Historic Site of Canada/Facebook)

She spent 17 years as a volunteer with the Doukhobor Dugout House. She wrote letters to elders and historians. She catalogued stories, artifacts and fragments of a fading culture. She dreamed up the Prayer Home, a quiet building organized with the reverence of a museum.

Even in the laundry, she left her mark. She used a rock rather than a washboard to clean clothing the traditional way at a small spring on the site. That rock is still part of the display but has sat unused since her death. Her ashes were scattered on the land she gave so much of herself to.

Inside the Prayer Home, garments draped over mannequins whisper of quiet rituals and old traditions. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Her voice still echoes there too, literally.

“When she passed away, I was going through Dan’s phone,” Cheveldayoff said. “And I said, ‘Oh my God, you recorded her.’ I wondered if I could take that recording and have it playing when people walk through. So today it’s set up that when people go through, you can hear her talk and do her part.”

A mannequin in the Prayer Home is dressed just like Choppe, apron and all. Even her lighter and cigarettes are still there, tucked in the pocket, exactly where she would have put them.

The mannequin dressed like Donna Choppe wears her apron and carries her cigarettes and lighter, left just where she would’ve put them. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

“It’s kind of a running joke,” Cheveldayoff said, but her eyes softened.

Because of course, it’s not really a joke. It’s love — preserved.

The calm in the ravine

As you make your way down the steep trail toward the dugout house, a quiet hush seems to fall. Cheveldayoff said the calm down here is part of why the spot was chosen as where her ancestors would settle.

“Once you walk down in the ravine, you kind of understand why they chose that,” she explained. “Because our prairie winters are cold and windy, and when you are out here in the winter, and you walk down there, it’s calm. Even on a Saskatchewan windy day. So it makes perfect sense why they built in the sides of the hills.”

The weathered buildings scattered across the property aren’t just ruins — they’re relics of resilience, where every board and nail tells a story of the people who made this land home. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

When Cheveldayoff walks the land, she often wishes she could walk it with her father one more time.

She imagines him baking bread in the outdoor oven again, guiding guests along the path, proudly sharing the stories he once passed down to her.

“It’d be nice to walk around with him when we’re doing dignitary tours and things,” she said softly. “It’s always on my mind here.”

The bread oven stands like a quiet ember of memory — a place where Brenda’s father once baked. (Doukhobor Dugout House National Historic Site of Canada/Facebook)

And maybe that’s what truly makes this place meaningful, not just the plaques or the national designation. But the feeling you get when you realize this isn’t just a historic site. It was someone’s home.

And while the archaeologists found their share of relics — fragments of dishes, tools, the traces of daily life — there are other artifacts here too.

In 2008, the Doukhobor Dugout House was named a National Historic Site of Canada — not for grand architecture or famous battles, but for the quiet courage of those who carved a home into the earth and chose peace over war. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

A bread oven, still warm with memory. A laundry rock sitting unused. A pack of cigarettes in a mannequin’s apron. A bag of wooden clothespins, right where Choppe left them.

Because of Cheveldayoff, this isn’t just a place where history is told. It’s a place where memory is kept alive in every step down the ravine.