Beside a quiet dock in La Ronge, a floatplane bobs gently on the surface of the lake.

It’s old, unmistakably so, its paint faded from decades of sun, wind and water.

The engine is loud, the cockpit small. The smell of fuel and oil hangs in the air like part of the landscape.

To most, the aircraft looks like a relic. To the Pacey family, it’s home.

Listen to the story here:

The 1956 Beaver floats quietly at the Rise Air dock — a familiar sight in La Ronge, and still in service after nearly 70 years on the water. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

This is a story about a plane, yes.

But it’s really about a father and son — Robert Pacey Sr. and Robert Pacey Jr. — and the lives they’ve built in northern Saskatchewan, working side by side for Rise Air in the sky and on the ground.

And at the heart of it all is an old de Havilland Beaver, built in 1956 and still earning its keep in the bush.

The community of La Ronge comes into view from the Beaver’s window, a place the Paceys have called home for decades. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Fuel in the blood

Jet fuel runs in the Pacey family’s blood. It always has.

Pacey Jr. was only eight the first time he flew an airplane… sort of. He was sitting up front in a Beechcraft Baron, a small twin-engine plane, on a flight home to La Ronge from Lynn Lake, Man. His hands were on the yoke from the right seat — the co-pilot’s side.

“There were no controls on my side,” he laughed. “But that was the first time I ever flew an airplane.”

For Robert Pacey Jr., the Beaver isn’t just a plane — it’s a calling passed down through oil-stained coveralls and wide-open skies. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

He was 15 when he started flying for real, and got his commercial license in 2022. But by then, it already felt like the path had been laid for years.

“I flew a bunch of different types of airplanes when I was younger,” he said. “It was something I always wanted to do.”

His dad, Pacey Sr., doesn’t just understand that instinct. He built a life around it.

“I started fixing planes when I was 12,” he said. “Hanging around the airport. Helping an engineer from Ontario with his airplane.” By 14, he was officially on the payroll, working the dock at Lake Manitoba. “They called me a swamper. They wanted somebody to load and fuel their airplanes. And no other dock hand wanted to do it. So I got to fly right seat of a Twin Otter all summer.”

Robert Pacey Sr. has spent a lifetime with his boots on the dock and his hands in the engine — a steady force behind every safe takeoff. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

It was grunt work, but it came with a front-row seat to the world of bush flying.

Before he had even graduated high school, the elder Pacey was approved to write his Transport Canada exams.

He came to La Ronge in 1989, walking into a hangar that still looks and feels much the same today. Same concrete floor. Same tools. Same air thick with the hum of work being done right.

And the same floatplane — a 1956 de Havilland Beaver, serial number 831 — the same one Rob Jr. flies today.

Moored along a northern shoreline, the Beaver waits for its next trip into the bush — still doing the job it was built for. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Still flying

They’ve kept the Beaver going through sheer stubbornness and skill. The engine — a 450-horsepower Pratt & Whitney R985 — is tough to find parts for. Only a handful of overhaul shops even touch them now.

But the plane is still out there doing what it was built to do: landing on rivers, flying into fishing camps, touching down in places where there are no docks, no roads — just rock, water, and sky.

In Rise Air’s fleet of modern aircraft, the Beaver stands out as a nod to the airline’s heritage reaching back to the 1950s.

The cockpit of the Beaver is tight and loud. It’s a place where stories begin, one throttle push at a time. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

“It’s pretty versatile,” said Pacey Jr. “We’ve landed on short strips, rivers, hauled canoes on the side. Wherever you need us. We got a lake? We’ll go.”

He’s flown all over the North — as far as Cree Lake Lodge, 160 miles out, and everywhere in between. On floats in the summer, skis in the winter. No two days the same. And every trip has one thing in common: the people.

“You’re taking people to places they love,” he said fondly. “They’re always happy. I’ve never flown around someone who wasn’t happy on a floatplane.”

The view from the back of the Beaver hasn’t changed much in decades — water, forest, and long stretches of sky. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

The plane might be old. But it’s the kind of old that comes with stories, not rust. The kind of old that still works — because someone still cares.

And no one cares more than the Paceys.

A father’s pride

For Pacey Sr., aviation was never just a career — it was a lifestyle. Something he shared with his family from the very beginning.

“I used to take my kids on road trips when they were knee-high to grasshoppers,” he recalled. “Weekends, we’d have to go fix airplanes. I told them, ‘If I can take my boys, I’ll go.’”

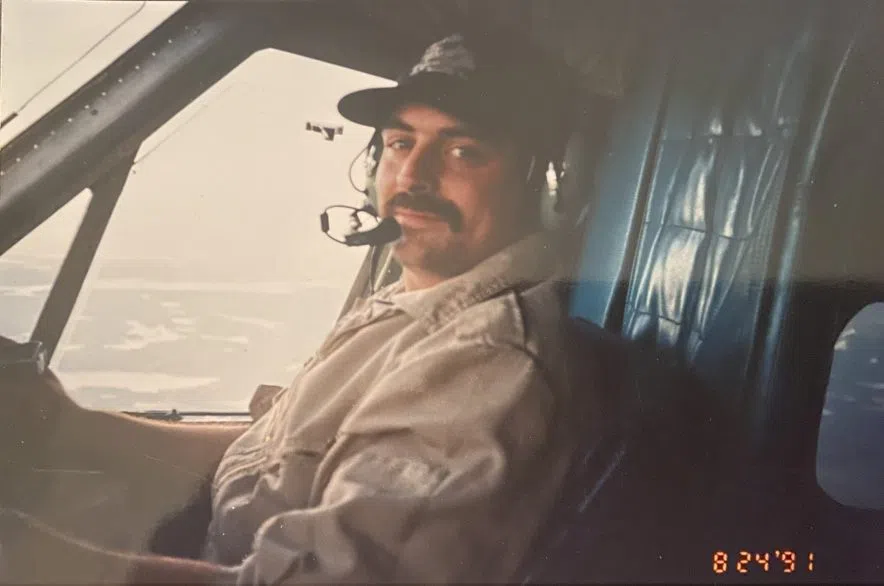

Robert Sr. was carving paths through the northern sky long before his son would one day follow in his slipstream. (Submitted)

He remembers one Father’s Day in particular — both sons in tow on a job up north. “By the time we took off, I looked back — they were both asleep. Worn out.”

Today, his son is one of the pilots captaining the planes he works on. The responsibility attached to that reality never fades from his mind.

“Even when I work on an airplane, I get apprentices to double check my work, and vice versa. We’re always checking each other’s work to make sure everything is properly put together and and working properly,” he said. “You want to make sure everything’s above board. Because you can’t just pull over near a cloud and open up the hood.”

Wrench in hand, boots wet from the lake. This is how it’s always been for Pacey Sr. An engineer, a pilot, and a caretaker of wings. (Submitted)

Not just a job

Aviation in northern Saskatchewan is much more than a job. It’s a lifeline.

From above, the effects of this year’s wildfires stretch across the land, a reminder of how quickly things can change in the North. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Planes carry nurses to remote communities, fishermen to the camps they dream about all year, sick patients to the care they need. The pilots and engineers who work in the north don’t just fly — they serve.

And for the Paceys, this work is about much more than flying or fixing a plane. It’s about each other.

Even when the lakes freeze and the floats are swapped for skis, the work doesn’t stop for the Paceys. (Submitted)

“I wouldn’t give it up for anything else,” Pacey Jr. said. “It’s been a lot of fun.”

His dad agrees.

“Proud,” Pacey Sr. said when asked how it feels to see his son in the pilot’s seat. “Very proud.”

Tied off at the dock in La Ronge, the Beaver is quiet now — but ready, as always, for the next call north. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Somewhere on a northern lake…

Somewhere today, that old Beaver is skimming across the water, its radial engine roaring as it lifts into the air — maybe bound for a cabin, a lodge or a makeshift dock made of rocks and pine.

The boy who once slept in the back seat is now at the controls. The man who first showed him the way is back in the hangar, checking and double-checking every bolt.

Some people inherit houses or companies or land.

But in the Pacey family? They inherit sky.