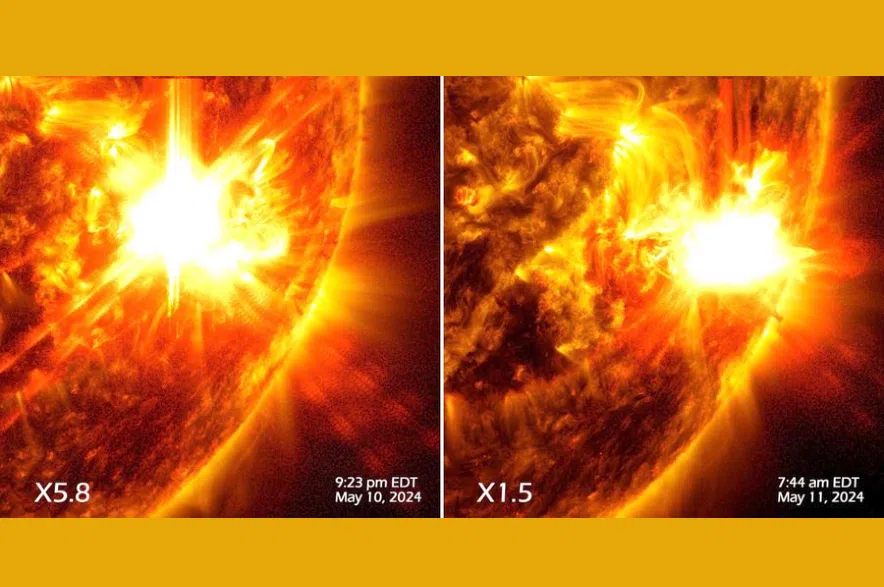

Powerful solar flares erupted on the surface of the Sun on May 10 and 11, spitting out a burst of radiation that caused short radio blackouts on the sunlit side of the Earth and spectacular northern lights.

Vassy Kapelos spoke to Jesse Rogerson, who has PhD in astrophysics and is an assistant professor of science at York University about if something like this could happen again.

The Vassy Kapelos Show airs on Saturdays and replays on Sundays on 650 CKOM and 980 CJME.

Read more:

- Astronomer: More Starlink junk likely to be found in Sask.

- Cost of Canada joining Trump’s Golden Dome missile defence project still unknown

- SaskPower’s first ‘microgrid’ now powering Descharme Lake

These questions and answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Vassy Kapelos: What is a solar flare?

Jesse Rogerson: The Sun is this gigantic ball of plasma that’s 100 times wider than the Earth and spins really fast. It generates a complex magnetic field, just like Earth has a magnetic field, but this one gets all tangled up and crazy because it’s a big ball of plasma.

Every 11 years, the Sun goes through this crazy tangling up of its magnetic field that generates these flares, which are just a release of magnetic energy, and basically shoots away the atmosphere of the sun that we call solar flares.

You can get little ones, you can get big ones and you can get massive ones, called coronal mass ejections.

The Sun is very active right now and it shoots flares out into the solar system in many directions, and we get hit all the time.

Kapelos: What are the threats, opportunities and challenges created by solar flares?

Rogerson: There are solar flares all the time but every once in a while there are some flares that are that are really strong, what we call the X class ones that are really bright.

Those ones have the potential to be threatening to us, particularly to our electrical infrastructure, meaning things like power grids and radio communication satellites are particularly vulnerable because they’re above or further up in the magnetic field of the Earth.

Those really strong ones that can happen every five to 10 years could maybe damage that infrastructure as the charged particles create a surge in electricity that shorts them out.

In the in the 1980s, we had blackouts in in a large portion of Quebec because there was a big solar flare, and part of the power grid got knocked out. Power lines needed to be replaced and power rerouted to account for that and it can be out for a few days if the flare is big enough.

The opportunities and challenges are to innovate, create power systems and communication systems that can handle being knocked out. You need redundancies, other ways to communicate and you need to be able to deploy solutions when and if it happens again.

Kapelos: What impact can solar flares have on on Earth’s weather and climate?

Rogerson: Not much. In terms of creating weather storms like tornadoes or hurricanes they are relatively safe.

What it does do is create aurora. When those big clouds of charged particles hit the Earth, they get funnelled to the poles by our magnetic field. They hit the atmosphere and creates northern lights like the ones in October 2024. That was an event of a similar strength to what happened last week when you get these X class solar flares.

Kapelos: How do you, as an astrophysicist build technology to deal with solar flares if you can’t put it in a laboratory?

Rogerson: To some degree we are a little bit helpless. You put a satellite in space to help you with communications and if that satellite gets shorted out you can put redundant systems on it.

You can have multiple computer systems and different ways of routing the power through the satellite, but if all of that gets shorted, then the satellite becomes dead and like, there’s not much you can do about that.

To prepare for situations where a satellite goes completely dead you have to have redundant satellites, meaning constellations of satellites, and this has been a huge push over the last like 20 years.

SpaceX is most notable for it but Canada has a strong interest in having networks of satellites, not just one satellite to do your communication, so that if one or two drop out you’re ready. A solar flare won’t necessarily knock out every single satellite all at once so the more redundancy you have, the safer you are on the ground.

It’s the same idea as if a weather storm comes, like an ice storm here in Canada, knocks out a power grid, you need to be able to to deploy people and infrastructure quickly to rebuild that.

Canadian power structures are prepared for ice storms. We know what to do when that happens. What we also need to be ready for is a random event in the middle of the summer, when an ice storm is not expected.

Read more: