For weeks, we’ve been hearing that the limiting factor in Saskatchewan hospitals isn’t necessarily the equipment but the properly trained health-care workers — and top officials of the SEIU-West union said that’s not a new situation.

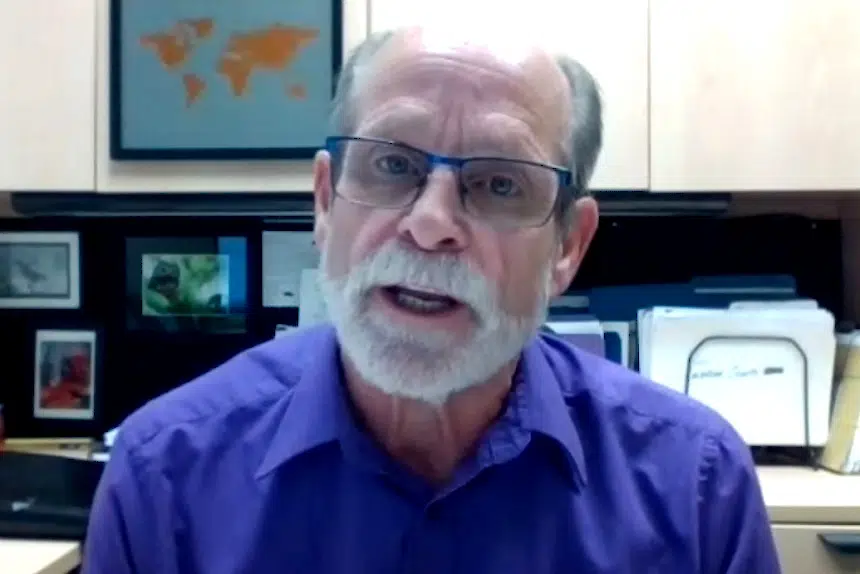

“SEIU-West has been telling (health officials) that we are understaffed in all of our facilities and classification for more than 12 years,” said Neil Colmin, the vice-president of the union that represents 11,500 health-care workers.

Colmin called the current work number unsafe and said it and COVID-19 are contributing to the situation the province is seeing in its hospitals. He said there has been “gross mismanagement” of the health-care system for years.

Union president Barbara Cape echoed Colmin’s words, saying staff in the health-care system are running full tilt because there are too few hands in everything from acute care to long-term care to home care.

“What this results in is incredibly dangerous work with regular assaults on health-care workers, surging cases in hospital with incredibly complex needs, and horrible stories about patients, clients and families turned away from care,” said Cape.

“We’re not on the brink of collapse and we’re not close to the edge. We are in a collapsing health-care system.”

Referencing patient transfers to Ontario, Cape said there is obviously a need because health-care workers are at 180 per cent capacity.

“Right now we don’t have the staff, whether they’re doctors or nurses or other health-care workers, to provide that care right now,” she said. “Talking with a number of folks who are members of the nursing team, we are providing COVID critical and complex care outside of the ICU and the struggle, quite frankly, is that not everybody has that skill set.”

Cape said the union has been ringing the alarm on the problem for years, using work tracking forms and meeting with ministers and the premier about it. She claims the Saskatchewan Party government has deliberately ignored the problem.

“Health-care workers of all stripes are calling on everyone in this province to demand better from our MLAs and premier,” Cape said. “We want people to call, write and visit their MLA and ask them to take responsibility for the mistakes that have been made but also provide clear and transparent plans for the path forward to get out of this pandemic.”

When it comes to burnout and workers leaving health care, Cape said she thinks the problem will be seen more down the line.

“They have a professional and an ethical commitment to continue to provide that care, but I think when the worst of the chaos of this pandemic has dissipated … what you are going to see are people leaving the system in droves,” explained Cape.

“We’ve already have a number of folks indicate to us that when this is done, they’re out. They’re leaving health care permanently.”

For those who stay, Cape said the need for mental health care is going to be significant.

“The struggle that we’re going to have is not just how do we manage health human resources to get us through the pandemic, the next question’s going to be how do we support those people who remain and how do we recruit people to the health-care system that has been devastated,” said Cape.