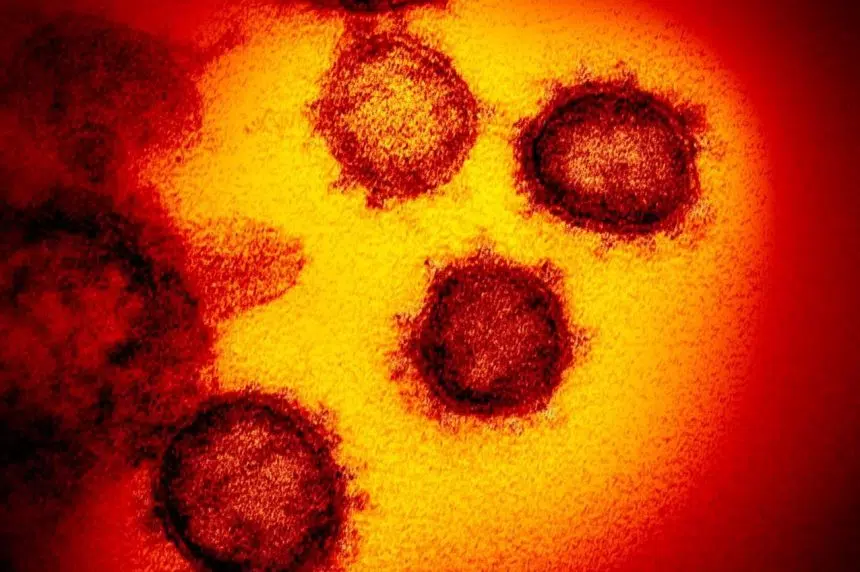

Researchers at the University of Saskatchewan are teaming up with employees at the Canadian Light Source and VIDO-InterVac to study the long-term effects of COVID-19.

Dr. Jake Pushie is used to studying strokes through his work with the College of Medicine’s Saskatchewan Cerebrovascular centre.

Pushie is now applying his expertise to look at what SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 do to blood vessels.

“A lot of what we were hearing sounded a lot to us like some of the things we’re used to studying using the synchrotron,” Pushie said of first hearing about terms like “brain fog” and other lingering neurocognitive issues after contracting COVID-19.

Researchers are sending images of brain, heart, lung and lymph node samples that had been infected with the coronavirus to the Canadian Light Source to have its advanced imaging tools examine the samples.

“It’s highly specialized stuff,” Pushie said, “the kinds of imaging we’re doing that we absolutely can’t do anywhere else in the country.”

The real interest of the study is to find out what happens to the body after people have recovered from COVID-19 and now have an immune response. Is a person predisposed to chronic problems or other health concerns 10, 20 or 30 years later?

“These are real significant things that can impact people well after they’ve recovered from COVID-19,” Pushie said. “This is the kind of thing that, going forward, we need to be prepared to grapple with.”

With data gathering in the early stages, Pushie and his team are taking the outlook that COVID-19 is creating health complications.

“Some of those changes have already been documented,” he said, pointing to research proving the “remodelling of the tissue around blood vessels,” making it harder for blood vessels to function properly.

“You may be fine while you’re young if you’ve had this kind of a remodelling event happen,” Pushie said. “That’s a permanent change that’s going to stay with individuals going into the future and that really will have a profound impact for some individuals.”

Heart disease, stroke and other issues are some of the complications Pushie highlighted.

The synchrotron will be able to identify if the metabolism of a certain organ has been affected by contracting COVID-19.

Pushie is hoping to publish the team’s findings as soon as it’s able to gather more samples from people who contracted the virus earlier in the pandemic.

“I don’t think we could underestimate the importance of having some of this information,” he said.

The study could help people who’ve recovered from COVID-19 understand long-term risks or complications.

The study could also map out risk factors for recovered cases or alter health recommendations in the future.