MONTREAL (AP) – Hundreds of thousands of Canadians have been unwittingly exposed to high levels of lead in their drinking water, with contamination in several cities consistently higher than they ever were in Flint, Michigan, according to an investigation that tested drinking water in hundreds of homes and reviewed thousands more previously undisclosed results.

Residents in some homes in Montreal, a cosmopolitan city an hour north of the U.S.-Canada border, and Regina, in the flat western prairies, are among those drinking and cooking with tap water with lead levels that exceed Canada’s federal guidelines. The investigation found some schools and daycares had lead levels so high that researchers noted it could impact children’s health. Exacerbating the problem, many water providers aren’t testing at all.

It wasn’t the Canadian government that exposed the scope of this public health concern.

A yearlong investigation by more than 120 journalists from nine universities and 10 media organizations, including The Associated Press and the Institute for Investigative Journalism at Concordia University in Montreal, collected test results that properly measure exposure to lead in 11 cities across Canada. Out of 12,000 tests since 2014, one-third – 33% – exceeded the national safety guideline of 5 parts per billion; 18% exceeded the U.S. limit of 15 ppb.

In a country that touts its clean, natural turquoise lakes, sparkling springs and rushing rivers, there are no national mandates to test drinking water for lead. And even if agencies do take a sample, residents are rarely informed of contamination.

“I’m surprised,” said Bruce Lanphear, a leading Canadian water safety researcher who studies the impacts of lead exposure on fetuses and young children. “These are quite high given the kind of attention that has been given to Flint, Michigan, as having such extreme problems. Even when I compare this to some of the other hotspots in the United States, like Newark, like Pittsburgh, the levels here are quite high.”

Many Canadians who had allowed journalists to sample their water were troubled when they came back with potentially dangerous lead levels. Some private homeowners said they plan to stop drinking from the tap.

“It’s a little bit disturbing to see that there’s that much,” said Andrew Keddie, a retired professor who assumed his water was clean after replacing pipes years ago at his home in Edmonton, a city of almost 1 million in western Canada. What he couldn’t do is replace public service lines delivering water to his house. After learning his water lead levels tested at 28 ppb, Keddie said he was “concerned enough that we won’t be drinking and using this water.”

Sarah Rana, 18, was one of tens of thousands of students who weren’t alerted when her brick high school in Oakville, a town on the shores of Lake Ontario, found lead levels above national guidelines in dozens of water samples, the highest at 140 ppb. She found out on her own, looking at reports posted online.

“I was getting poisoned for four years and did not know about it,” she said. “As a student, I think I should be told.”

Leona Peterson learned of the contamination in her water after journalists found excessively high lead levels in 21 of 25 homes tested in her small, northwest port town of Prince Rupert. Peterson, who lives in subsidized housing for Indigenous people, had water that registered at 15.6 ppb.

“I was drinking from the tap, directly from the tap, without any knowledge that there was lead in the water,” said Peterson. Her son was as well. Her response: “Hurt, real hurt.”

The town of Prince Rupert, where whales, grizzly bears and bald eagles are common sights, is among more than a dozen communities along Canada’s wild west coast where residents – many Indigenous – are living in homes with aging pipes, drinking corrosive rainwater that is likely to draw lead. But their province of British Columbia doesn’t require municipalities to test tap water for lead.

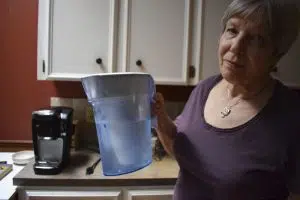

Monica Baehr holds a Zero Water filter for drinking water at her home in Calgary, Alberta, Canada on Aug. 6, 2019. Hundreds of thousands of Canadians from coast to coast have been unwittingly exposed to levels of lead in their drinking water, with contamination in several cities consistently higher than they ever were in Flint, Michigan, according to an investigation that tested drinking water in hundreds of homes and reviewed thousands more previously undisclosed results. (Mackenzie Lad/Institute for Investigative Journalism/Concordia University via AP)

Canadian officials where levels were high said they were aware that lead pipes can contaminate drinking water and that they were working to replace aging infrastructure.

And some localities are taking action. Montreal Mayor Valrie Plante vowed to test 100,000 homes for lead and speed up replacement of lead-lined pipes immediately after journalists sent her an analysis of the city’s internal data revealing high lead levels across the city.

The media consortium filed more than 700 Freedom of Information requests and took hundreds of samples in people’s homes to collect more than 79,000 water test results. But the findings are neither comprehensive nor an indication of overall drinking water quality in Canada. That doesn’t exist.

“Because there is no federal oversight, everybody does what they want,” said engineering professor Michle Prvost, who quit working on a government study of school drinking water in frustration over the lack of lead testing. “Most provinces ignore this very serious problem.”

The government’s approach to limiting lead in drinking water in Canada is starkly different from the U.S., where the Environmental Protection Agency sets legal standards under the federal Safe Drinking Water Act, and every person is supposed to receive an annual Consumer Confidence Report from their water provider by July 1 detailing lead test results.

There’s no similar, routine testing or notice in Canada, with the exception of the 14 million-person province of Ontario, bordering the U.S. and the Great Lakes, which post results online.

“If that’s not public, that’s a problem,” said Tom Neltner, a chemical engineer at the Environmental Defense Fund, a U.S.-based environmental group. “The public is more sensitive to the risks of lead, especially on children’s development. Where you have transparency you have advocacy, and where you have advocacy you have action.”

In the U.S., however, even public water quality reports weren’t enough to prevent the Flint, Michigan, drinking water crisis, brought on by a 2014 decision to temporarily pull water from a river as a cost saver while installing new pipelines. Some doctors raised concerns in Flint after noticing elevated lead levels in children’s blood tests. Flint’s water problems went well beyond lead: Excessive microbes turned the water reddish brown and led to a Legionnaires’ disease outbreak that caused at least 12 deaths and sickened more than 90 people.

The Flint crisis sparked congressional hearings, lawsuits and scrutiny of lead testing across the country. Now officials in Newark, New Jersey, are scrambling to replace about 18,000 lead lines after repeated tests found elevated lead levels in drinking water.

Other communities are also responding. Nearly 30 million people in the U.S. were supplied drinking water that had excessively high levels of lead, from Portland, Oregon to Providence, Rhode Island between 2015 and 2018, according to an analysis of EPA data by the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental group. Hundreds of people in the U.S. are suing local water authorities over the contamination.

Virginia Tech professor Marc Edwards, whose study of the Flint water system helped reveal the dangerous lead levels, reviewed the Canadian media consortium’s findings.

“This is a significant health concern, people should be warned,” said Edwards. “Something should be done.”

In Canada, where lawsuits are less frequent and provinces – not the federal government – set water safety rules, the main source of lead in drinking water is antiquated pipes. At one government hearing, an expert estimated some 500,000 lead service lines are still delivering water to people in the country.

Some cities, like Montreal, are already working to replace them, tearing up streets and sidewalks with massive and expensive construction. But homeowners are almost always responsible for paying the cost of replacing the section of pipe between their property lines to their homes, a cost that can range from about $3,000 to $15,000, according to provincial studies.

Several other short-term solutions include having suppliers add anti-corrosives or altering water chemistry so it’s less likely to leach lead from the insides of pipes as it heads for the tap. These are widely used and often mandatory in the U.S., but in Canada only the province of Ontario requires anti-corrosives in communities with older buildings and sewerage.

Studies have documented over years that even low levels of lead exposure can affect a child’s IQ and their ability to pay attention. Children who are younger than 7 and pregnant women are most at risk from lead exposure, which can damage brains and kidneys.

Yet the consortium’s investigation found daycares and schools are not tested regularly. And when they are tested, those results are also not public.

Documents obtained under the Freedom of Information laws included a 2017 pilot study of tap water at 150 daycares in the picturesque, lake-laden province of Alberta. It showed 18 had lead levels in drinking water at or above 5 ppb, which the researchers considered risky for the infants and toddlers. The highest was 35.5 ppb.

Canada is one of the only developed countries in the world that does not have a nationwide drinking water standard. Even countries that struggle to provide safe drinking water have established acceptable lead levels: India’s is 10 ppb, Mexico and Egypt’s are 5 ppb, according to those country’s government websites.

Joe Cotruvo, a D.C.-based environmental and public health consultant active in the World Health Organization’s work on drinking water guidelines, hadn’t realized that some provinces in Canada don’t routinely test tap water for lead.

“Really? No kidding,” he said. “In the U.S., if there is a federal regulation, states are required to implicate it. If they don’t, they’re functioning illegally.”

Drinking water testing and treatment methods are also inconsistent in Canada.

In the U.S., in-home tests are taken first thing in the morning, after water has stagnated in pipes for at least six hours. This provides a worst-case scenario, because after water runs through pipes for a while, lead levels often decline.

In Canada, provinces have set their own rules, which range from not testing at all, to requiring a sample to stagnate before testing. Few are treating the drinking water itself to lower lead levels.

Maura Allaire, an assistant professor of water economics and policy at University of California, Irvine, was surprised Canada’s major water suppliers aren’t routinely required to add anti-corrosives to drinking water.

“Yikes, I could imagine in older cities if they’re not doing corrosion control what can happen when acidic water touches lead pipes in homes,” she said.

She recommends Canadian officials start to address the problem by collecting better information.

“Once you have better information, there can be targeted efforts, to really try to prevent corrosion,” she said. “The big discussion in the U.S. among politicians is to replace the pipes, but that takes time and is costly. If there’s lead in the water, you’ve got a public health problem that needs to be dealt with now.”

By MARTHA MENDOZA, The Associated Press