It was 107 years ago that the Titanic sank in the icy waters of the Atlantic Ocean.

The ship certainly doesn’t look the same now, as one Regina resident knows all too well.

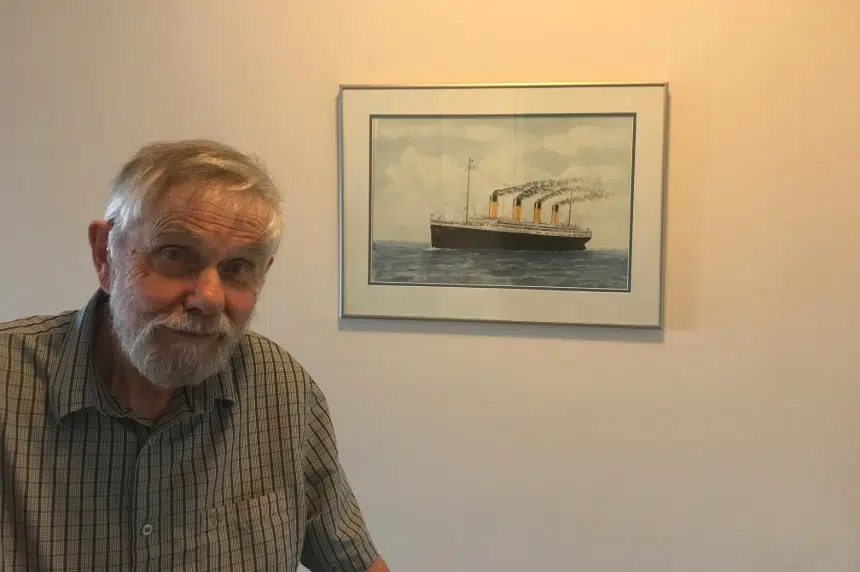

Roy Cullimore, 83, is one of the world’s foremost experts on iron bacteria, having looked at how microbes cause corrosion in shipwrecks.

“Where (the Titanic) sank in the middle of the Atlantic, there weren’t a lot of nutrients and it’s really the nutrients which cause the steel to degrade faster,” said Cullimore. “The nutrients that are significant for the Titanic are the steels, where you’ve got seven per cent (or) nine per cent phosphorus right in the steel. The microbes will sense the phosphorus … and they will actually drill in to get at the phosphorus.”

Cullimore called the steel on the Titanic the “energy source” for the microbes, which spread rapidly over the shipwreck as it’s a significant nutrient source for the bacteria.

The bacteriologist — who now runs the water-testing company Droycon Consulting in Regina and continues to work full time — said he became intrigued by the depths of the ocean during his university studies.

“When it comes to water, there’s zero knowledge; it’s all ignorance and that’s why I moved into that field,” he said. “When everybody else totally ignored them, I thought, ‘Well, this is an interesting group’ … I started with the the iron bacteria about 1973 or 1975, and I developed the method for looking for corrosion in that.”

Cullimore’s first venture to the Titanic was in 1996, when he managed to see up close the shipwreck and the colonies of microbe bacteria eating away at it.

He described seeing what he calls a community of microbes as “mindboggling.”

“(I thought) ‘They’ve managed to do that? They’ve managed to grow this big?’ ” Cullimore said with a laugh. “You’re talking in terms of microbes making a colony that is now two, three (or) six feet long and a foot wide and it’s all microbes in there.”

Cullimore’s expertise even allowed him to work with James Cameron on the film ‘Titanic’ in 1998. He said the director had a particular interest in the Turkish baths of the ship, which Cullimore got to see.

“From a microbes point of view he chose well …,” Cullimore said. “Two of the walls in the Turkish bath look just like when it sank (and) the other two are rotted completely. Why? It’s one of the many questions that have come out of my experience with the Titanic.”

Cullimore ventured to the shipwreck again in 2003, 2004 and 2005 but wasn’t able to get up close and personal like his first time.

He said the ship has broken into three main parts, and the communities of microbes have reacted differently to each part.

“(In) most of the middle section, the microbes have been really hungry and (are) taking the steel out from that,” he said. “The stern section, it’s still pretty well intact and the bow in the front, the microbes are playing games there (and are) mainly inside.”

Although the Titanic might be the most famous wreck he has seen, Cullimore said he has done some work studying iron bacteria on some Second World War shipwrecks that stick out to him, particularly a German U-boat sunk in the Mississippi delta.

“That one has been steadily degenerating,” he said. “But when you think of the steel on these submarines (it’s) thick … When you compare it to the Titanic, the steel on the Titanic was half an inch at best and when you go to the (U-boat), well, you go up to three-quarters of an inch or even an inch.”

Even though it has been over a century, Cullimore said it’s still going to be a long time before the shipwreck disappears completely.

“I would say if you look at the parts, the stern probably will last intact for another thousand years, simply because of the big engines,” he said. “The midsection is pretty well gone today (and) when you look at the bow section … it’s probably going to be a hundred years before the bow breaks apart.”

At 83 years old and still working full-time hours at his business, Cullimore said he has no plans of slowing down.