TORONTO — Gord Downie only appeared in public a handful of times in 2017, but his calls for a more inclusive Canada resonated even in his absence.

Whether it was the poignant lyrics flowing through his recent albums or the heartfelt words he delivered in public, the Tragically Hip singer used every opportunity in his final months to speak out in support of Indigenous people in Canada.

Even after he died of brain cancer in October at age 53, Downie’s push for reconciliation continued to reverberate across the country.

His hope for a better Canada is one of the reasons editors and broadcasters say they selected him as Canada’s Newsmaker of the Year for the second straight time.

Downie collected 47 votes (53 per cent) in the annual Canadian Press survey of newsrooms across the country. The musician remains the only entertainer to receive the title in its 71-year history.

He’s also now among a select group of Canadians to be voted top newsmaker more than once. Others include former prime ministers Lester Pearson and Pierre Trudeau and activist athletes Terry Fox and Rick Hansen.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was second in this year’s poll with 11 votes (13 per cent), while new NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh finished third with 10 votes (11 per cent).

“Most Canadians don’t really care about politicians — but Gord Downie seems to have touched so many hearts,” wrote Christina Spencer, editor of the Ottawa Citizen’s editorial pages.

“Rarely have we mixed our tears of sadness and gratitude as we did for Gord Downie,” added Danny Kingsbury, national rock format director at Rogers Radio in Ottawa.

“His music and legacy and work with Indigenous communities will live on.”

Even though Canadians knew it was coming, news that Downie had succumb to an incurable form of brain cancer on Oct. 17 left many stunned.

It almost seemed at times like he could do the impossible — somehow defy science to overcome his terminal diagnosis.

He surprised doctors and fans alike with his boundless determination during the 2016 Hip tour. At the rousing last concert in Kingston, Ont., Downie offered hints of his next vision. Speaking to the audience, he expressed the urgency of drawing more attention to the inequities faced by Indigenous people. He called on the prime minister to lead by example.

Downie’s “Secret Path” multimedia project, which was completed before his cancer diagnosis, became the guidebook in his last year as he delicately recounted the tragic final hours of Chanie Wenjack.

For many Canadians, it was the first time hearing the story of the 12-year-old Ojibway boy who died of starvation and exposure after escaping a residential school in 1966.

“His spirit touched Chanie Wenjack’s spirit,” said Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde.

“Even though they never physically met each other, I think in a spiritual way they knew and really bonded together.”

Alvin Fiddler, the Grand Chief of the Nishnawbe Aski Nation, worked closely with the Downie family over the past year and a half. He said it was impossible to predict how “Secret Path” would affect the wider conversation.

“None of us really could envision the impact,” he said. “To see it spread across the country was something … pretty meaningful.”

Fiddler credits Downie for shining a spotlight on some Indigenous issues, which he said led to progress in certain areas.

“We have more and more communities coming off the boiled water advisory list next month in Slave Falls,” he offered as one example.

“I would like to believe that Gord had a hand in those things.”

Exploring the injustices inflicted upon Indigenous people in Canadian history led the singer on a personal journey of reflection, said his brother Mike Downie.

“Gord said several times that the only thing that mattered to him was getting Canadians to become aware of Indigenous lives, start to right the wrongs and move in the direction of reconciliation,” he said.

“It was what he wanted to get done before his time was up.”

As the year stretched on, the reality of Downie’s mortality was harder to ignore. His appearances became increasingly rare.

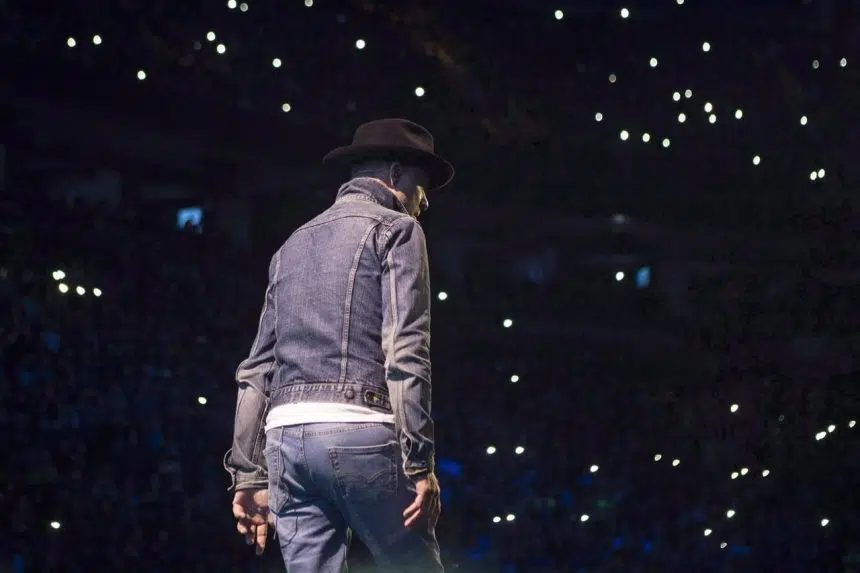

He surprised Blue Rodeo concertgoers in February by walking on stage to sing “Lost Together” alongside Jim Cuddy and other close friends. The emotional moment would be Downie’s final public stage performance.

In June, he was appointed a member of the Order of Canada for his work in raising awareness of Indigenous issues.

On Canada Day weekend, Downie stood on a stage at Parliament Hill and encouraged a young crowd of We Day participants to ask questions about the history of residential schools. He emphasized that Indigenous children in some parts of Canada continue to travel great distances each day for school, likening it to “the pain, the torture and the death” in residential schools.

His comments stood to elevate concerns Indigenous leaders have expressed over the lack of education and health resources for young people in remote communities.

“It is still happening even though the residential school has gone away,” the ailing performer said.

“It’s time to listen to the stories of the Indigenous. To hear stories about now.”

He left the audience with an optimistic final thought as he looked to the next 150 years for the country.

“Yours is the first generation in the new and real Canada. I love you,” he said to applause.

“You and yours, the Indigenous, together will make this a true country now, one true to your word. The new 150 years, not the old one. The new one. Exciting and true.”

A few months later, he was gone.

On the streets of Kingston that sombre October day, the hometown boy’s voice was everywhere. Restaurants cranked up playlists of only Hip songs, while some fans blared their car stereos to drown out the pain of the loss.

Many talked about how Downie offered solace amid their family’s own cancer fights. Others reflected on how their perspectives of Canadian history were reshaped by his ardent support of Indigenous rights.

Those sentiments stretched across the country as local musicians covered Hip favourites and viewers watched a broadcast of “Long Time Running,” a documentary recounting the band’s final tour.

More Downie tributes are still in the works. A public memorial is being considered by the Hip’s members and their management, though no official date has been set.

And in Ontario, an opposition NDP member recently introduced a bill to create a poet laureate program in the province and name the legislation after Downie.

Carrying Downie’s message into the future now lies with his friends and the millions of Canadians he called on to make a difference.

The late singer established the Gord Downie and Chanie Wenjack Fund to serve as a catalyst in the movement towards reconciliation. Next year, the organization plans to escalate its approval of small grants that would unite Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities and promote education in schools.

It’s a project Downie considered essential for the longer term. He’d witnessed slivers of progress while he was still alive, his brother Mike said, and he considered each of them a reason for hope.

“He could see that he had some impact,” Mike Downie said.

“I know Gord felt really good that he had maybe managed to move the needle a little bit.”